Donation Stories

Kristen Adele Willoughby: A Breath of Fresh Life

In April 2011, Kristen Adele Willoughby underwent a life-altering double lung transplant at St Vincent's Hospital in Sydney. At the age of 33, after living with Cystic Fibrosis since childhood, Kristen's journey to this pivotal moment was fraught with challenges and a growing dependence on medical interventions, including round-the-clock oxygen in the months leading up to her transplant.

In April 2011, Kristen Adele Willoughby underwent a life-altering double lung transplant at St Vincent's Hospital in Sydney. At the age of 33, after living with Cystic Fibrosis since childhood, Kristen's journey to this pivotal moment was fraught with challenges and a growing dependence on medical interventions, including round-the-clock oxygen in the months leading up to her transplant.

Diagnosed with Cystic Fibrosis, Kristen's condition progressively deteriorated until, by 2009, a transplant became her only viable option for survival. Her reaction was one of acceptance and understanding of the necessity of this complex procedure. After a relatively short five-month wait, Kristen received the call that would pave the way to a new chapter in her life. Despite the surgical challenges of removing her fused lungs, the operation was a success, leading to a swift recovery.

A New Lease on Life

Post-transplant, Kristen describes her health as "fit and healthy," a stark contrast to her pre-transplant days of limited mobility and constant care. She is now an avid runner, often found in her home gym or participating in long-distance runs, a feat impossible before her transplant. This newfound vitality has allowed her to be more present for her son, transitioning from a bed-bound existence to an active, engaged parent and community member.

Post-transplant, Kristen describes her health as "fit and healthy," a stark contrast to her pre-transplant days of limited mobility and constant care. She is now an avid runner, often found in her home gym or participating in long-distance runs, a feat impossible before her transplant. This newfound vitality has allowed her to be more present for her son, transitioning from a bed-bound existence to an active, engaged parent and community member.

One of the most profound changes Kristen has experienced is the elimination of the time-consuming treatments that once dominated her daily routine. The absence of nebulisers and other treatments has freed her to enjoy activities like walking up hills or climbing stairs without breathlessness, which she now takes on with gusto.

Kristen is not only back to enjoying life but is also setting ambitious goals, like running a marathon, which speaks volumes about her resilience and determination. Her appreciation for her donor is immense, recognising the gift of life she has received as something that has allowed her son to grow up with a mother by his side.

A Voice for Donation

Kristen actively advocates for organ and tissue donation, emphasising the transformative impact it can have not just on recipients but on entire families. Her message is clear and powerful: registering as a donor is one of the most selfless acts someone can perform.

Kristen's story has captured the attention of media outlets such as NBN News, the Gold Coast Bulletin, and ABC Radio, particularly following her participation in marathons—a testament to her remarkable recovery. Her presence on social media and various podcasts continues to inspire and educate about the importance of organ and tissue donation.

Today, Kristen is planning to tackle the Gold Coast Marathon and complete her 10th half marathon—milestones that mark not just the distance she can run but the distance she has come from her days of uncertainty to a life full of possibilities and achievements.

The Heart of a Hero: How One Donor Saved Jayden’s Life

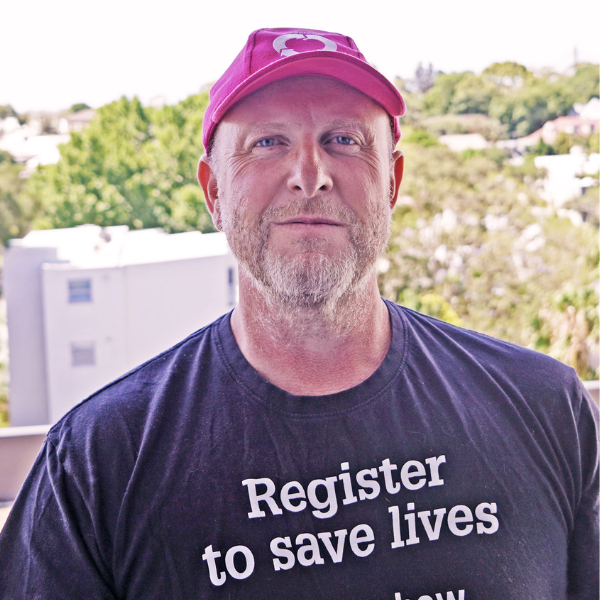

My name is Jayden Cummins, a 51-year-old dad from Sydney. I've always loved staying active, and there's nothing better than spending an afternoon in the cricket nets with my 14-year-old son.

My name is Jayden Cummins, a 51-year-old dad from Sydney. I've always loved staying active, and there's nothing better than spending an afternoon in the cricket nets with my 14-year-old son.

But life took an unexpected turn in August 2017. Like many Australians, I caught the flu—and thought little of it. However, the virus silently attacked my heart. As the days went by, I felt worse, so I took myself to my local hospital. Things escalated quickly, and within days, I was in a coma, connected to ECMO (full life support), and rushed to St Vincent's Hospital. My heart gave up, along with my liver and kidneys.

I wasn't healthy enough to receive a heart transplant straight away. My only hope was an artificial heart to keep me alive until a donor heart became available. I flatlined during the procedure, but the incredible medical team at St Vincent's brought me back. When I woke up weeks later, I was alive—but with a mechanical heart keeping me going.

Being on the transplant list was a strange mix of hope and uncertainty. I dreamed of watching my son grow up, marry, and maybe even become a dad someday. That hope gave me the strength to live life more fully than ever before. But I couldn't escape the weight of knowing that when the call came, it would mean another family was facing the deepest grief imaginable. I often wondered about my future donor. Who were they? What were they doing at that very moment? And if I could meet them, what would I say? I never knew if it was strange to think that way—but the thoughts stayed with me.

Then, one Sunday morning in early 2019, everything changed. At 4:30 a.m., I answered the call that saved my life—a heart had become available. Sitting with my family at St Vincent's Hospital, waiting to go into surgery, we felt a complex wave of emotions. We were hopeful. We were grateful. And we were heartbroken. Somewhere in another hospital, a family was saying their final goodbye to someone they loved. Yet, in the middle of their grief, they honoured his decision to donate his organs, giving me a second chance.

There are no words to fully express the gratitude my family and I feel toward my donor and his family. A donor's heart feels like a heart already filled with love and generosity. My mission now is simple: to keep it full.

Thanks to their incredible gift, I get to watch my boy grow up and live a life I never thought possible. Just last weekend, I was back at the cricket nets with my son, doing what we love.

The gift of life is the greatest gift one person can give to another. It crosses every boundary—race, gender, creed, or class. It's an act of pure humanity. To the families who honour their loved one's decision to donate, you are heroes too. Thank you from the bottom of this beautiful heart.

Second Act

At 193 centimetres, he towered over everyone and was renowned for his generosity of spirit.

When his neighbours lost their homes in the nearby Lismore flood in Northern NSW, David was there by their side, helping them rebuild from the ruins.

The banker and triathlete met his wife Alisa later in life when they were in their 40s, and they savoured every moment of their time together.

It was no surprise to Alisa when David told her he wished to be an organ donor. “That was so typical of him – he loved helping people. He was a giver,” she recalls.

Little did they realise that she would be honouring his wishes just ten years later. David was 56 years old when, out of the blue, he suffered a fatal brain bleed. His heart, kidneys, liver and pancreas cells went on to change the lives of five people.

“I know this may sound bizarre, but during the testing process, each time we received news that one of Dave’s organs was viable for donation, I felt a glimmer of something that wasn’t quite grief,” Alisa recalls. “Each time I was thinking, ‘Go, Bear,’ (her nickname for him).”

Police escorts are often used between regional hospitals and airports when no other suitable transport is available. But it seemed particularly fitting that David’s organs would be taken that way to Ballina Airport. Alisa watched from the top of the main road in Lismore with her mother and sister as the police cars zoomed past, lights flashing and sirens wailing.

“Of course, he received a police escort out of our town; that was Dave to a tee, going out with a big splash. I could almost hear him laughing and asking why they hadn’t put up a statue in the main street of town in his honour too.”

Alisa finds it difficult to convey her gratitude for the Lismore DonateLife team. “There are no words to describe the support, patience, and understanding that we received from them.”

“Losing David has been the most gut-wrenching, worst experience of my life, but his choice to donate his organs has changed how I have grieved for him. I miss him terribly. I miss his humour and our weekly date nights. I miss the way he was my biggest supporter. But he has left a legacy that has been gaining momentum every day since he passed.”

“Friends and family have started to have conversations, and they are difficult conversations, but they need to happen. It’s important to ask your loved ones: ‘What do you want once your life on earth has ceased?’”

“If David could see how his actions have affected family, friends and total strangers, I think he would be totally humbled,” she says.

On a Clear Day

Sydney teacher Maria Boyd will never forget the palpable relief she felt as she walked through the doors of Sydney Eye Hospital and into the care of ophthalmologist Dr Con Petsoglou.

Sydney teacher Maria Boyd will never forget the palpable relief she felt as she walked through the doors of Sydney Eye Hospital and into the care of ophthalmologist Dr Con Petsoglou.

“Never before have I been so thankful for being in Australia,” Maria recalls. “For Medicare, for Dr Petsoglou’s care, for our high level of health care. It was the first time in three months I felt held.”

That was in July 2021.

Maria and her husband Ben had been teaching in Vietnam when her world began to turn dark – quite literally. Maria developed a chronic infection in her left eye. COVID-19 began to cut its swathe around the world. International borders began to slam shut.

To make matters worse, Ben had to suddenly fly home to visit his father who had been diagnosed with stage 4 liver cancer.

Not only was Maria’s eye infection difficult to treat – as well as excruciatingly painful – it was potentially fatal.

“Once the infection took hold, I understood why sailors had once committed suicide due to the pain,” she said.

Neither the hospital nor the eye clinic in Ho Chi Minh City had the equipment or skills to help, so Maria, who by this stage had grown “profoundly afraid”, boarded a plane to Sydney.

Then a little miracle occurred. After months of treatment, staff at the Sydney Eye Hospital were able to curtail the infection, and Maria found herself being prepared for a corneal transplant.

The morning after the bandage was taken off will be etched indelibly in her mind for as long as she lives. “I opened my eyes. The vision had returned. It was blurry, but I could see,” she recalls.

“How could I possibly capture in words just how miraculous and life-changing that is?”

“Dr Petsoglou is not just a world expert in this very rare condition, he is the very best of human beings.”

Today, Maria is still slowly adjusting to her new vision; she just started pulling goggles on and swimming in her local ocean baths. She is also working again, as a mentor to teachers and senior students.

“I’m deeply joyful and truly thankful to be in Australia where transplants are possible for every Australian,” she said.

“I am so deeply and profoundly grateful to be the recipient of this priceless gift,” Maria said. The corneal donation, she says, was “one of the most humane acts of giving – a timely reminder of how selfless and generous human beings can be.”

New Beginnings

Ruby Payne was just eight years old when her dad noticed her heart was racing. A visit to the GP led to a diagnosis of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension, a rare and life-threatening condition.

Ruby Payne was just eight years old when her dad noticed her heart was racing. A visit to the GP led to a diagnosis of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension, a rare and life-threatening condition.

Doctors at Westmead Children’s Hospital did everything they could, but her condition worsened. Ruby’s heart, lungs, and liver began to fail. She struggled to walk more than 30 metres without resting.

The only option left was a double lung transplant—and thanks to an organ donor, Ruby received one in time.

Today, Ruby is in Year 7, walks five to six kilometres a day, and hopes to return to netball. Her family is forever grateful to the donor who gave her a second chance.

“They gave this precious gift to our daughter at a time of incredible pain and grief,” says her father Robbie. “Ruby’s beautiful smile is what kept us going.”

Unintentional hero

“I miss everything about Tony, even the annoying things. If there was just a half drunk coffee cup in our shed I promise I wouldn't be annoyed. I would be so happy.”

“I miss everything about Tony, even the annoying things. If there was just a half drunk coffee cup in our shed I promise I wouldn't be annoyed. I would be so happy.”

These are the words of Brenda Pratt, who lost her childhood sweetheart and beloved husband in October 2021 after suffering a stroke.

“I miss his laugh, his cheeky smile. I miss how much he loved us all. I miss his ability to be able to do anything it seemed, and now I have to do those things on my own. I am grateful that a 17-year-old boy loved me until he was 53 years old, for his confidence to say yes to everything.”

Amidst the waves of grief has been the consolation that Tony was an organ donor.

Tony Pratt was a born leader who had forged deep connection with all his family and friends. To give in death is exactly what almost anyone who knew him would expect.

“Tony had a giving nature, so it was his last act of giving,” she said.

Brenda, as well as their daughter Ebony and son Hayden have derived comfort from the thought that people would be seeing because of his corneal donation and that other people’s lives have changed for the better including a lung recipient.

“I like the thought of looking into a random person’s eyes knowing part of Tony might live on in them,’ Brenda said.

After serving in the RAAF for more than two decades working on fighter jets, Tony ran a cattle and crop farm with Brenda in Kyogle, in far north east of NSW. He also delivered mail, earning the nickname Postman Pratt, and was renowned for helping many people along the way, whether it be changing the tyre of a stranded motorist or helping a cow give birth.

Tony was an avid football player and coach, loved fixing things and most of all loved playing with his grandchildren Harper and Nate particularly their favourite game of “chaseys”

When Tony’s family were asked about donation, they did not hesitate.

“We knew it meant that someone had to be having a better day than us somewhere, getting the miracle that we didn't,” said Brenda. “We know that he would have loved that.”

First kidney transplant between HIV positive donor and recipient marks a milestone for HIV patients

When one lucky transplant recipient, let’s call him Ken, was diagnosed with HIV in 2006 he thought he would die from the disease.

When one lucky transplant recipient, let’s call him Ken, was diagnosed with HIV in 2006 he thought he would die from the disease.

Fast forward 17 years and Ken is not only alive – he is better than ever thanks to a recent kidney transplant from an HIV positive donor.

In an Australian first, staff at Sydney’s Royal Prince Alfred Hospital performed a kidney transplant between a donor and Ken who were both HIV positive.

The RPA Kidney Transplant team performed the operation on the patient who received the kidney transplant on an unintentionally fitting date –World AIDS Day.

Ken had been on dialysis for renal failure for several years. With a wait list for kidneys averaging at about six years, his life was becoming increasingly grim.

“Being on dialysis is like travelling through the desert,” he said. “The scenery doesn’t change and you don’t know how long your going to have to keep travelling along that straight line.”

Facing an unknown length of time on dialysis, Ken felt himself sliding into despair.

“After a while it became too painful to go on,” he said. “I seriously considered letting renal failure claim my body and checking into palliative care instead.”

The day he received the call that a kidney from an HIV positive donor was available was an unforgettable one.

“It was the day my life suddenly began to have a sense of hope.”

The transplant went extremely well and Ken is enjoying every moment of his “new life” as he calls it. “I can’t thank the medical experts around me enough for giving me such a great second shot at life. All I can say is I feel blessed by what’s happened to me.”

“This is wonderful news for the HIV positive community,” says Dr Michael O’Leary, the co-State Medical Director of the NSW Organ and Tissue Donation Service.

“HIV does not preclude you from being placed on the organ transplant waiting list – although some modifications of HIV medicines may be required, the results are the same as for non-HIV patients,” he said.

“This also means that people living with HIV and organ failure can safely receive an organ from a HIV positive donor.”

“Everyone is eligible to register as an organ and/or tissue donor on the Australia Organ and Donor Registry regardless of their HIV status,” Ms Danielle Fisher, General Manager of the NSW Organ and Tissue Donation Service said.

A person’s sexual orientation, gender, gender identity or expression does not prevent that person from becoming an organ or tissue donor.

A man who has had sex with a man can register to be a donor.

Everyone wishing to donate organs and tissues will be considered - organ donation is not the same as blood donation, as it is always matched to a specific patient.

Tissue donation is similar to blood donation. It is regulated by the TGA and subject to additional requirements. This is because tissue products are prepared for the general population and stored rather than being matched to one recipient in the same way that organs are.

All potential organ and tissue donations are valued and considered, including those from LGBTIQ+ people.

New treatments for historically life- limiting diseases such as Hepatitis C and HIV are increasing the opportunities to consider organ donation. Potential donors are assessed on a case-by-case basis for risk factors to ensure transplant patient safety.

“This means more and more people can donate their organs and HIV positive organs can help improve or save lives,” Ms Fisher said.

“The more organs we have for transplant the more lives will be saved.”

For every organ donation, the overall health or condition of organs, as well as compatibility with potential recipients can vary and is considered case by case.

But in general, a typical kidney from someone with HIV positive status can have excellent function in an HIV positive recipient who has kidney failure, Dr O’Leary said.

Ken says organ transplants such as his “roll back years of stigma”.

Being able to receive an organ from an HIV positive donor can enable a shorter wait for a transplant.

As Ken puts it: “It gives our community a sense of hope. We can now go into a hospital when we are HIV positive. It gives you a lot to live for. You can become a donor. You can change lives. All is not lost. Registering to donate is a great way to help our community.”

For more information on organ donation and the LGBTIQ+ community, see our LGBTIQ+ Donation page. You can register as an organ and tissue donor on the Australian Organ Donor Register.

A path with heart

Emily Smith will never know of the stranger who saved her life.

Emily Smith will never know of the stranger who saved her life.

But as she holds her little son Hudson in her arms, she remains forever grateful for their gift.

“My son still has his mum because of the kindness of a stranger,” she says.

Six weeks after giving birth to Hudson, the 26 year old’s world came crashing around her when she discovered she needed a new heart – and fast.

She was struggling to walk from the living room to her bedroom without being out of breath. At times she would gasp for air, she lost her appetite and there were multiple occasions where she thought she was going to faint.

Tests showed that she had peripartum cardiomyopathy – a form of heart failure that happens up to five months after giving birth.

Placed on the emergency transplant list, Emily was added to both the Australia and New Zealand directories.

Luck was on her side, and after just a week and a half, she received a perfect heart match.

Her old heart was successfully removed and the new one took its place.

Two weeks later, Emily walked out of hospital, elated to be given a second chance at life.

Emily is now a committed advocate of organ donation.

“I don’t really think of it as someone else’s heart,” she says. “It is my heart but it just took a different journey to becoming my heart. Words cannot express the gratitude I feel to the unintentional hero who saved my life, and kept my family together”.

Tom's gift

A Year 12 student with a big future in academic studies, sport and music, 17 year old Tom van Dijk tragically suffered a fatal cardiac arrest following a swim with his family near their home on Sydney’s northern beaches.

A Year 12 student with a big future in academic studies, sport and music, 17 year old Tom van Dijk tragically suffered a fatal cardiac arrest following a swim with his family near their home on Sydney’s northern beaches.

But Tom’s story doesn’t end there. Tom and his generous family gifted his kidneys and corneas to improve the lives of others. Tom’s kidneys were successfully transplanted into one man and one woman. His corneas also went on to restore sight to seven people.

For Tom’s girlfriend Caitlin, his death was the end to many plans and dreams but his generous and compassionate spirit lives on.

The pair had met on the school bus at the end of 2019. Romance blossomed, and they quickly became inseparable.

After they’d finished school, Tom and Caitlin were planning to travel around Australia in a campervan before buckling down to study at university.

“Tom was so generous, so compassionate, so funny, and so engaged in life. We just got on so well together,” said Caitlin, who has continued to be warmly embraced by Tom’s family.

“Tom was one of those incredibly special people. He brought so much joy and love into my life. I just feel so lucky to have met him.”

It was when Tom was getting his learner’s permit that he asked about organ donation at the dinner table.

“Tom made it clear that he wanted to support organ donation and it was so typical of him to want to help others in need,” said his father Brad. “In hindsight, we are so grateful that we had the discussion as a family.”

Brad and Tom’s mother Karrie did not hesitate following their son’s wishes after he passed away. “It’s what Tom would have wanted; to be able to help others,” said Brad.

Caitlin was not surprised when she discovered her beloved was an organ donor.

“All Tom wanted to do was help people, and in his final moments that's exactly what he did. I never knew one person could care so much about the people he loved, and even people he hadn't nor would ever meet.”

Last year, Tom’s parents wrote a letter to each of the recipients, hoping they were happier and healthier than ever.

“While losing him was so shocking, and we still feel the pain, he was a blessing to us and we are so incredibly thankful for the privilege of having him in our lives, and knowing he lives through you.”

Birth of the new

Sydney environmental lawyer Sarah Mansfield was dismayed to discover she had vasa previa whilst pregnant with her daughter Lara several months ago.

Sydney environmental lawyer Sarah Mansfield was dismayed to discover she had vasa previa whilst pregnant with her daughter Lara several months ago.

Not only did the condition potentially put both mother and baby in danger, but it also put an end to her plan of having a natural birth as she did for her first child, Max, who is now a boisterous 29-month-old.

But thankfully, Sarah found herself in the care of what she calls her “dream team” of doctors and specialists at The Royal Hospital for Women Randwick.

Under the careful watch of the hospital’s director of obstetrics, Dr Andrew Bisits, and Fellow Dr Sara Ooi, it was arranged for Sarah to have a caesarean section.

The birth went extremely well and donating her amnion membrane, or thin layer of tissue from the placenta, she said was the “silver lining.”

“The care I received at The Royal was exceptional, so when I was asked by Dr Ooi if I was interested in donating, I jumped at the opportunity.

“All I had to do was fill out a form and it meant the amnion didn’t go to waste. It was easier than donating blood. I love the thought of it being able to help someone, whether they are conducting research or otherwise need a skin graft.

Sarah’s amnion is just one of the many that have been donated to the NSW Tissue Bank.

Since late 2018, women giving birth via elective caesarean at the Mater and The Royal Hospital for Women have been able to donate their placenta tissue, also known as the amniotic membrane, to be used as a surgical dressing for patients at Sydney Eye Hospital.

Sarah’s was the first from the Royal Hospital for Women. Thanks to the fact that one donation can generate 30 grafts, the NSW Tissue Bank will soon hit a milestone of 1000 amnion recipients.

Amnion donations are used to heal corneal ulcers, chemical burns, eye diseases and other wounds.

Dr Con Petsoglou, medical director of the NSW Tissue Bank and a surgeon at Sydney Eye Hospital, who has been coordinating the program, said the “bio bandage” worked because it is a foetal tissue, full of healthy molecules that help healing.

The method dates back to at least the 1960s, when it was uncovered by US eye surgeons entering Cuba who learned that local doctors had been dressing wounds with a mysterious substance purchased from Russia. Tests revealed the material was placenta tissue.

For the past eight years, Australian hospitals have been purchasing tissue donated through hospitals in Auckland. But now between 15 and 20 Sydney women like Sarah choose to donate their placenta each year.

Second chances for a gentle giant

Thanks to an organ donor, a father of two little girls has been given a new lease on life by a kidney transplant.

Thanks to an organ donor, a father of two little girls has been given a new lease on life by a kidney transplant.

Throughout his adult life, Chris Enahoro has been plagued by kidney disease.

The 40 year old former Souths centre, partner of Megan and father of two girls Thea and Matilda was diagnosed shortly before his 18th birthday.

For more than two decades, Chris, known to many as Maroubra’s gentle giant, battled with nausea, fatigue, insomnia, gout, weight gain and loss of appetite. Due to the medication he also developed shingles, pneumonia, high blood pressure, fluid retention. At one point Chris’s strapping 195 cm frame ballooned in weight and he put on 35 kilograms.

In 2022 things started looking hopeful: he started dialysis after his sister Elizabeth offered to donate her kidney. But then his world came crashing down around him again when a few weeks before the operation, he was told his sister’s kidney was not suitable for the transplant.

While tackling these health challenges, and spending months in and out of hospital, he continued to maintain his career as a rugby league player in NSW and Queensland, and more recently, as a personal trainer.

Finally in May 2023, Chris received the call he’d been waiting for - a large kidney from a deceased donor in Perth was available for transplant.

Chris says he is now more energetic than he has been in years and is deeply grateful to the NSW Organ and Tissue Donation Service.

“The day after the surgery I could see better and smell better. It felt like a fog had been lifted,” he says.

Chris encourages anyone who will listen to register for organ donation.

“The biggest thing I’ve noticed is my relationship with my friends, family and my kids. They haven’t known me healthy. They’ve known me most of my life being unwell and sleeping most of the time. Now I can go to the kids’ sports and coach their teams. It’s been amazing.”

Chris is also keen to get back out into the surf at Maroubra, relishing the dawn ritual of watching the sun rise over the Pacific ocean, savouring every moment of what he calls “his new life.”